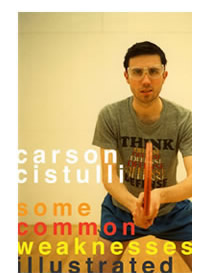

Some Common Weakness Illustrated, Carson Cistulli’s first book, is a series of unexpected meditations on overlooked parts of life.

Combining formalism with poetic experiment, his poems shed light on his peculiar condition of feeling that he is trapped inside of a poem while being addicted to sports-basketball and baseball in particular. In these poems language seems to replace meaning, while feeding our spectacular, collective appetite for the truth.

Yale Series Poetry Award Winner, Loren Goodman writes: Carson Cistulli’s book of poems is like the rabbit that pulls the magician into his hat. It is like an enormous handkerchief spewing out colorful severed hands. It is like the woman who uses her naked body to cut saws in half.

For a larger cover image, click here

Purchase

Book Details

Publisher: Casagrande Press (June 1st, 2007)

Paperback: 88 Pages

Size: 5.5″ X 8.5″

ISBN: 0-9769516-1-4

ISBN 13: 9780976951612

Price: $10.95

About Carson Cistulli

Cistulli received his MFA from the University of Massachusetts. He has also attended Columbia University in New York, where he studied with Kenneth Koch, and the University of Montana, from which he graduated with a BA in Classical Civilization.

He was born in Concord, NH. Currently, he hosts a not unpopular radio program called Goal: The Soccer Show out of Valley Free Radio in Florence, MA. Cistulli is skinny, sports-obsessed and lacks fashion sense. He is 27 and lives in Northampton,

MA. His work has previously been published in the following journals: The Hat, Cold Drill, canwehaveourballback, and Free Radicals: American Poets Before Their First Books; additionally he published a chapbook Assorted Fictions (Chuckwagon Press).

Book Reviews

Dip into it as you would throw the I-Ching. Or as you would stumble, weeping, into the self-help aisle, grab a book, and look for answers. Each line is crafted for your improvement. — Pioneer Valley Arts

PRAISE FROM THE POET LOREN GOODMAN

I am struck by the poems of Carson Cistulli.

They strike me repeatedly about the head, face

And heart. Sometimes they beat me with a smile

Sometimes they caress me with their wickedness

I try to get up but they get me again in the gut

As he says, “It hurts at first, but then feels good—

sometimes even better than before.”

Carson Cistulli is an actor.

His poems are his films.

I like the popcorn.

Carson Cistulli’s book of poems

Is like the rabbit

That pulls the magician

Into his hat

It is like an enormous handkerchief

Spewing out colorful severed hands

It is like the woman

Who uses her naked body

To cut saws in half

It is also like the shy child

Who emerges from the audience

Extending his hand ever so slowly

To feed the rabbit Trix

It is also like the bowl of Trix

That is not for kids

…………………………………………………………………………………….

Sample Poems

COMPOSITE SKETCH OF MY ILLNESS

1. I’m separate from the author. Like a moth, I have fur on my back.

Like a lawyer, I’m the product of two quick scams. I can’t see

beyond the poem in which I’m trapped. Like the dead, I have no

heart. Like an athlete, I’m optimistic. Although this paragraph is

ending, something doesn’t end. I’ll give you one guess.

2. The parable started with a Spanish inventor stapled to an ad for make-up. It ended with the discovery of magnetite in the ear of a philosopher. The decades in between feature a legless chair, a thoughtless son, and only one Super Bowl champion: your New England Patriots.

3. He was made handsome by the light of the toll plaza. Passing through the night beside Iowa’s premier designer, his beard grew an inch every minute, and the place he’d come from seemed to call his name: Richard Brinsley…

4. He spent his entire adult life searching for what rhymes with “decaf.” The answer could only be found by asking an arrhythmic child. At some point the eye becomes a mirror and not an eye. Its possessor sweats profusely and cites his own work when answering questions about the existential dilemma.

5. The plot took place. A man in a suit washed his car from fifty feet away. A bluebird landed on a Caesar salad without public recourse. From our knees we saw Boston, but from our backs we saw her breasts cascading down. By “we” I mean myself plus everyone in Tokyo. That’s the thing about Tokyo: I love them, but I’m not in love with them.

6. Silence is a business, you better believe it. There’s a sale on cerebral cortexes. You never thought you’d see that word pluralized, but it happens—to Ramirez, and to Jesus—and that’s all I can say on the topic of “What are you thinking right now, Carson?”

7. I took Latin in a small room. The parachute opened before the instructions said. When you can taste your own lungs, what does that mean?

8. I epoxied myself to a ruins. The mystics came to browse my pockets. Heaven lurked more closely than usual. My bones were crumbling one by one. Read on if you want, but it only gets worse.

9. My nephew was the lawyer who represented Death. Man, people are really trying to sue these days. Take this bus driver, for example. He accidentally sat in the ejector seat. Now he parts his hair on all different sides. This is happening all the time, and we don’t even know. And Christ won’t even stop by for a little savioring.

10. I was in preparation for an air conditioner contest. You sit in a cold room and give a lecture on the human heart. My secret is to slip drugs into my socks. I radiate the principles on which the universe was founded: if it’s close, embrace it; if it’s far, blow it up. Of course, the opposite is true and also will suffice.

11. Don’t let me see you in your miniskirt of emeralds. I’ll tell you the equation. Emeralds equal my eyes and your skirt equals the entire world to me. The entire world to me equals your pubis. It’s convoluted, hard to prove, and signifies nothing: just like a man who rushes after little girls in the amber light. I might’ve said this before. And also, I might’ve said this again.

JIRI WELSCH, NBA PLAYER

1. I’d just finished my poem for Jiri, the room filling with the light off a newspaper. The TV was turned to a commercial for medication that helps you throw a tighter spiral. Then it was turned to a cable channel wholly dedicated to naming your children. My room was festooned with the entrails of other failed poems: this one about the patron saint of internet browsing, another one to the government official in charge of two thumbs up.

2. When I finished my poem for Jiri, I realized I’d completely forgotten the videos. One was an instructional tape on how to hit the cold-blooded shot. The other was a comedy about a guy who dances with the whole school as back-up. Then the place was closed when I got there. “I needed that like a hole in the head,” I told my girlfriend when I came home. To which she replied: “My name is Kali, so put that in your poem, for chrissakes.”

3. When I finished my poem for Jiri, I had bogeys at six o’clock. Then, after some clever maneuvering, they were back at one. “Man that was a fast seven hours,” I told my wingman back at the base. To which he replied: “You’re a regular time-traveler!” From then on, that was always a big joke between us. Later, he even read my poem for Jiri and gave some clever suggestions. Interestingly, he was writing his own poem—for Cavs big man Carlos Boozer, whose aura or something had always really impressed me.

4. I finished my poem for Jiri at noon and by 3PM was already back on the coast. The waves rolled in like answers to the SAT. The sky was overcast as Emily Dickinson’s wardrobe. In one poem, she uses the phrase “body of work” in a suggestive manner. In another, she uses her own hair as an escape mechanism. “That would take years to learn,” I said after I read it the first time. Then I went and taught my beard to speak French. Even as I shaved it later on, you could hear the diminutive “mon dieu”s ringing and ringing out from the vicinity of my newly-shorn chin.

5. When I finished my poem for Jiri, I read that Tomaz Salamun one about the Rhode Island-Connecticut basketball game. He goes on to describe the three-point shot as “the period to end all sentences.” After that, I read an account of someone’s normal day, except it’s written in Middle English. In it, some rather intelligent armies clash by night: no you are, Matthew Arnold! The waves outside were like tasteless suppers. The sky was overcast as hotel/motel management. The painter in the story was just beginning a new series—it’s of women and men stricken with heartburn, searching over these high plains for effective relief, stat.

6. When I finished my poem for Jiri, I was to going to leave the café and play video games. Instead, I stayed there and thought about Vancouver while some girls in back celebrated. Later, I was supposed to attend a party, but instead fixed a tire that I myself had flattened. When would my fave pen run out?, I wondered. When would the winning streaks end? Outside, the waves rolled in like introductory offers. The sky was overcast as tiresome metaphors. An actor played all the parts himself to a theater of empty seats. Rapturous applause. Unanimous victory. Anyone could be this country’s next great general.

7. When I finished my poem for Jiri, I found myself in someone else’s poem entirely. First, I was at a World Series that never happened, deliberately spilling beer on my own self. Next, I was at the abandoned air strip of an Arctic village. “Hello,” I said to the natives, but they only greeted me with looks of woe and sorrow. Then it changed the subject abruptly to where I was an academic fluent in German. “Gutentach, Lebensweisheitspielerei”: what was I saying? I don’t know about that, but the assembly I was addressing loved it. Vigorously they applauded as I went backstage, where I noticed the part in my hair had changed and was mortified.

8. When I finished my poem for Jiri, I found the part in my hair had changed from left to right. Strangely, it was not a symbol at all—but only an everyday occurrence. Under it, my face looked panic-stricken and screwed-up, war-torn and history-laden. Turning to my poems, I saw they were all signed “Anon,” “Anon,” “Anon.” My phone number slowly disappeared from the book. And even now I saw I had a cleft chin, a cleft lip, even a cleft note. Grasping the conductor’s baton, I turned to the orchestra, which waited with holy optimism. They needn’t have even known their instruments that day, they were so rife with inspiration—or, literally, a “breathing into.”

9. When I finished my poem for Jiri, I also wrote one like Hesiod, Theogony. In it, “The God of Breakfast Cereals wedded the Goddess of Commuter Radio, who then bore the Gods of Electric Razor Technology and Business Casual along with the Goddesses of That Not-So-Fresh Feeling and also Fast-Acting Relief.” Later on, “The God of Post-Game Analysis, along with his cronies Empty Rhetoric and Retarded Catch-Phrase, raped the Goddess of Acute Observation, who then bore The God of My Creative Powers, a sickly waif tormented constantly by Nervous Temperament and Boston’s Offensive Woes.” Outside, the waves rolled in like scenic end tables. The sky was overcast as women, conspirators in causing difficulty.